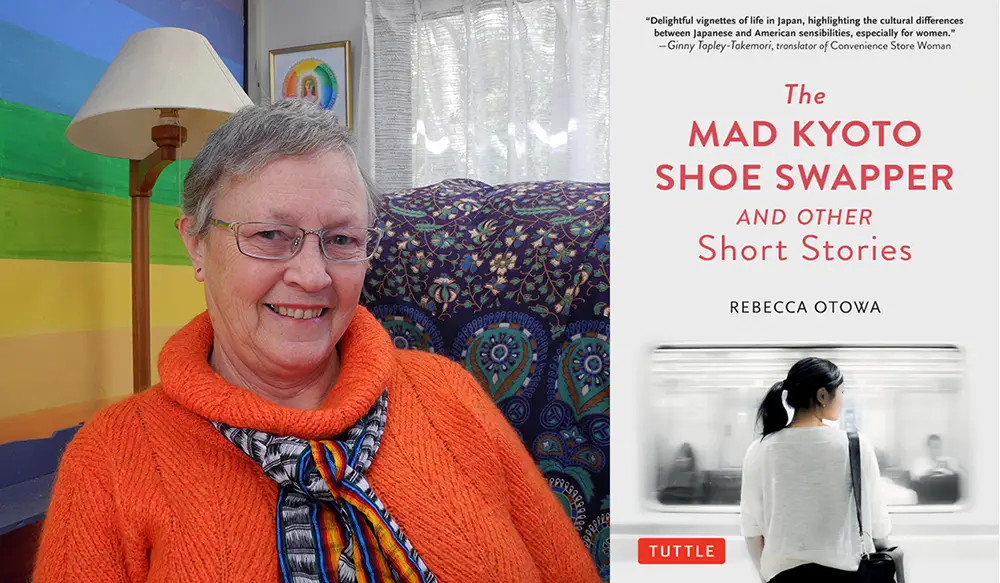

Rebecca Otowa is an American-born, Australian-reared, and Japanese-educated writer and painter who has been calling Japan home for the past 40 years. She has written extensively for several English-language publications in Japan and Tuttle published her first two books, At Home in Japan (2010) – the author’s true life story and journey from California to Shiga -, and My Awesome Japan Adventure (2013) – a book for children in the form of a fifth grader’s diary.

In this interview we will discuss Rebecca Otowa’s third book, The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper and other Short Stories (Tuttle Publishing, 2020), a collection of 13 stories about love, work, marriage, death, and family conflict in Japan.

Voicu Mihnea Simandan: You have lived what for some is a lifetime in Japan and have experience first hand who the Japanese are. Who are they to you?

Rebecca Otowa: For the past 35 years or so, I have been living in a small village southeast of Lake Biwa in central Japan. So the Japanese people I have the most dealings with are my neighbors. There are many differences between generations here; the older generation (my age) are polite, interested in keeping the old ways alive, slow to change (they have seen a lot in their lifetimes!), and friendly to me because I have been an active member of village life all along, both before my mother-in-law’s passing in 1999 and afterward. (It was her house I moved into, and we lived here together with her for 12 years.)

Japan is a small country but it does have regional differences. Since I live in Kansai (west Japan) and not in Tokyo, and because it’s an area steeped in history, the people here tend to take on the coloration of the ancient capital of Kyoto. I learned greetings and ways of speaking that would fit in with that older generation because that was how I was taught by my mother-in-law, though younger people are now not as punctilious about these things. I don’t have too many people I would count as friends, but I would call them perhaps colleagues — fellow villagers, neighbors. Other than that, I have dealings with my husband’s family, and they have accepted me as much as they are able, which is a great deal. I have always been treated as a member of the family.

VMS: Apart from actually living in Japan, you have also studied Japanese language and culture, as well as Buddhism. Looking back, what was the “aha-moment” that completely turned your life towards Japan.

RO: When I was 12 years old, my family migrated from Southern California to Australia. It was time for me to enter middle school, and I had an interview with the principal of my local school at which he asked me if I was interested in entering a pilot program of Japanese language then in its 2nd year. I said yes, mainly because I was fascinated by the idea of being able to write the characters. At that time, I didn’t really have a feeling toward Japan as such. That opportunity was what changed my life. Of course at the time, I had no idea what that decision would lead to.

VMS: Your latest book, The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper and other Short Stories is your first volume of fiction. What do these stories mean to you?

RO: I wrote these stories over the course of about 8 years. They emerged gradually, coming from various ideas and inspirations. Some were stories I heard from friends, some were drawn from my own experiences, some were imaginative accounts of things that happened long ago. I’ve enjoyed working on these stories because it’s a chance for me to delve deeply into the hearts of characters, both Japanese and Western, to feel what it’s like to be another person in another life.

And I don’t make outlines of plot. I just go where the characters take me, and sometimes the journey is very surprising. Because it’s fiction, I don’t have to write about myself but can write about someone else. Even though the characters are, strictly speaking, my invention, they do take on a life of their own.

4. VMS: The title story The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper brings to light the odd hobby of a reclusive man of stealing shoes from temples. How has your understanding of the Japanese psyche helped you in crafting these intriguing stories?

RO: Knowing something about how the Japanese think and what they feel about things has been a help to me in writing. For example, in the case of the protagonist of the title story, I knew that Japanese people have a consciousness of boundaries — where a certain area stops and another begins, in their physical world. Any place where shoes or slippers are taken off or changed is such a boundary, so anything pertaining to footwear has to be important to them.

When I myself experienced someone walking off with my own shoes by mistake at a temple, it made me think that there must be people in Japan for whom the act of changing or removing shoes takes on particular psychological significance. That was the basis for the story line.

Another example is in the story titled “Love and Duty”. The Japanese wife in that story hides a potentially fatal illness from her family in order to maintain its status quo. I think this is a very typical response to a private problem, especially for women — they are expected to hide anything that is wrong and deal with it in private. Sympathy for problems is not very forthcoming in the traditional culture. Such psychic features of Japanese society are things that one absorbs over the course of years, they are not immediately apparent to the visitor.

VMS: You have also used your own family history as the source of ideas. Tell us more about the 1619 land dispute which you write about in Trial by Fire.

RO: A land dispute arose between two local areas, East (my husband’s ancestral place) and West, in 1619, and it was decided to hold a trial by ordeal to settle it. By that time, the notion of such a trial was quite old-fashioned and in fact they had been outlawed by the central government. This trial required a special dispensation. The land dispute itself was about the rights to use the resources of the nearby mountain. Mountain resources, including timber, charcoal, and various wild plants, mushrooms and game, were very important to the people of long ago.

A stranger, who was staying in the Western part, suggested that the Western people should try to gain rights to the mountain which arose from the Eastern part. My husband’s ancestor was chosen as one of the two opponents to undergo the ordeal, which was like a single combat, and had religious significance, thus it was held in a Shinto shrine; and the stone tablet commemorating the trial still stands today at the same shrine. This kind of continuity of place is one of the most attractive things to me about Japan, especially rural Japan.

VMS: The stories in this collection present life from both the point of view of Japanese women but also of American ones. What was it like for an American woman to marry into a Japanese family in the 1980, when you married Toshiro Otowa, your Japanese husband?

RO: Well, that would fill a book by itself! First I guess I should say that I approached this adventure — getting married and joining a Japanese family — from the standpoint of Buddhism, which I had been studying in Kyoto. I decided that the best way would be to think of it as a kind of training, much like that undertaken by monks at a temple.

I had a slogan: “Every day an opportunity to learn.” At that time (things have changed a lot since) the local society was very rigid, with people exchanging greetings in set phrases, carefully balancing gift exchanges, not showing much emotion, getting the job done and trying not to bring shame on the family.

I think the hardest thing for me was not showing my emotions. I was constantly getting in trouble with my mother-in-law for what she called my “bad face”. Because of these two things — entering this life from a Buddhist viewpoint, and living in a very conservative family and area — I don’t think I had the kind of experiences that a “typical American woman” might have.

One must keep in mind, where individual human beings are concerned, there is no such thing as typical. I learned from being a member of a group called Association of Foreign Wives of Japanese that there are lots of ways for a foreigner to join a Japanese family. Perhaps my way was one of the difficult ones. You also have to remember that to say “a Japanese family” covers an extremely broad range of experience. My particular experience was of a very long-lived, historical rural community. Not the same as an apartment in the middle of Tokyo!

VMS: How about now? How do you see the interaction between foreigners and the Japanese in today’s world?

RO: In general I think there is still a lot of resistance to accepting foreigners into everyday life here. But things have changed a lot. For example, the expression “kokusai kekkon” (international marriage) isn’t heard much any more. I know several families around here that have members married to non-Japanese. Also, many Japanese young people have an opportunity to travel to other countries, and they bring back a wider view of the world.

How could this relationship be improved? I would like to see more realistic English teaching in the schools — not so tied to entrance examinations, with one answer being correct and everything else marked wrong. That is not how languages work. Most older Japanese people are afraid of English because it has always been seen as a way to be judged in examinations, not as a tool for communication (which is vital these days, as most of the Internet, international business, etc. are conducted in English).

This outdated idea of English is one reason why Japanese lag far behind other Asian countries in this ability. I’m sure it is different in places where there are a lot of foreigners living, but where I live is rural — there are only a handful of us in my area, but that is still more than when I came here, when I was completely alone.

I don’t think in general that there is as much prejudice against individual foreigners now as in the old days — the general reaction seems to be shyness and embarrassment. There is also quite a bit of pride in their own culture; everyone has that, but in Japan it reaches ridiculous levels sometimes. Japan definitely needs to work harder to be part of the global community — it is possible without sacrificing what they think of as their “uniqueness”.

VMS: The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper and other Short Stories is illustrated with your own black-and-white drawings. Having in mind that you’ve already had two shows of panting in Shiga (2015 and 2019), is art a separate form of expression or does it fuel from your writing?

RO: Drawing was my first love, and writing came later, though I did both from a very young age. When I was crafting the original version of my first book, I definitely enjoyed the illustrating more than the writing. I think a book without pictures is boring — much as Alice in Wonderland said. “’What is the use of a book,’ said Alice, ‘without pictures or conversations?’” I would like to see more illustration in books for adults. It keeps the eyes and mind from strain. I enjoy both types of self-expression very much, though if pressed, I would still say that drawing is more satisfying. Though most of my book illustrations are drawn from life, my paintings are more imaginative and fantastical.

VMS: In Three Village Stories you depict the life of three villagers, including that of a tea ceremony teacher. Among the Japanese arts, which form of expression has had the biggest influence on you as a writer and artist?

RO: I have direct experience with only one of these arts — the tea ceremony. Fortunately for me, an extensive study of tea includes many disciplines, such as flower arrangement, textiles, pottery, metalwork, calligraphy, and aesthetics in general. What I love most about the tea ceremony is the harmony that can be achieved through movement and the careful placement of utensils relative to each other. It is very much an art that involves both space and time. I try to keep this in mind both in drawing and writing. Keep moving but don’t be frenetic; organize things carefully; allow spaces to appear; leave something to the imagination.

VMS: Your collection of stories tackles some very important issues that the Japanese society faces today, from suicide, to anxiety, to loneliness, to obsessions. As a long-time resident of Japan, how has the Japanese society shaped who you are and how have you navigated the intricacies of such a complex culture?

RO: When I visit relatives abroad, they often comment that I have “become too Japanese”. It does get into the blood, and comes out in everyday life, in things like formality of language and action, placement of objects, arrangement of food, etc. At the beginning I think I internalized a lot of Japanese psychic issues; as I have gotten older I have felt happier rediscovering and expressing my own self.

Some of that self must of course be colored by Japan, but I have become more aware of where and when that happens, so I can control it. One thing I have learned is that different people expect different things from a social interaction, and I can now give people what they expect, be they foreign residents of Japan or Japanese people. In the case of Japanese, I can sometimes add a judicious dose of my true self, as I have learned what that is, in order to show them that there are other ways to be human.

VMS: Thank you for your time.

RO: You are welcome, thanks for giving me the opportunity to express myself.

Find out more about Rebecca Otowa’s work on her website.