This paper attempts a bird-eye-view presentation of critical pedagogy. It starts by trying to define critical pedagogy and its main features, and then continues with a brief presentation of the theories and theorists that highly influenced critical pedagogy. The final part of this paper outlines a few concepts that I consider important if we take into consideration the implications of critical pedagogy in the classroom.

Key words: critical pedagogy, teaching, Paulo Freire, Frankfurt School

Critical pedagogy has been shaped by numerous philosophical ideas and continues to be expanded and transformed through the work of contemporary educators. Because the term has undergone many revisions and transformations, researchers cannot come up with just one definition of critical pedagogy. To Kincheloe (2004) critical pedagogy is “the concern with transforming oppressive relations of power in a variety of domains that lead to human oppression” (p. 45). According to Darder et al. (2003), “critical pedagogy is fundamentally committed to the development and evolvement of a culture of schooling that supports the empowerment of culturally marginalized and economically disenfranchised students” (p. 11).

Traditionally, critical pedagogy is an educational theory that raises the learners’ critical awareness regarding social conditions that are oppressive. Through critical pedagogies, researchers strive to create a society based on egalitarianism, understanding and acceptance of its members, regardless of race, colour, and religion. Thus, critical pedagogy also has a political component as pedagogues struggle to challenge and hopefully transform oppressive social conditions.

Although challenged by its critics as being a highly theoretical endeavor, critical pedagogy is also concerned with teaching and learning practices that empower and give agency to students. The classroom component of critical pedagogy is evident in its concern with teacher – student relationships, and its constant challenge of the teacher’s role as the ‘all-knowing’ and the student’s role as the ‘passive receiver.’ Critical pedagogy argues for a classroom where meaningful dialogue produces new experiences for both the teachers and the students.

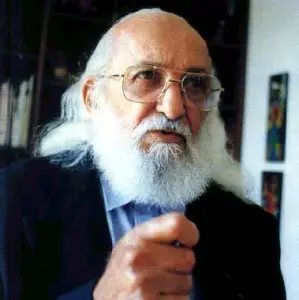

The most renowned critical educator is the Brazilian Paulo Freire, whose emancipatory work can be traced to the critical theory of the Frankfurt School. A major component of Freire’s work was the focus on the development of a critical consciousness. The liberatory education advocated by Freire prepares the students for engaging in social struggles that challenge oppressive social conditions. It is hoped that by empowering students with the necessary tools for critiquing oppressiveness, a more just society will be formed (Freire, 2003).

With time, Freire’s critical pedagogy has been expanded and transformed into theories that shifted the focus from class to include race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, nationality, etc. Thus, new theories have emerged, among which feminist, postcolonial, postmodern, and homosexuality are just a few. These new theories maintained Freire’s emphasis on critique, challenging oppressive regimes and social change, but have also adopted postmodern ideas of identity, language, and power.

Critical pedagogy theory was highly influenced by the following theories and theorists: The Frankfurt School, Paulo Freire, postmodernism, and Henry A. Giroux.

The “Frankfurt School” refers to the work of the Institute of Social Research, founded on February 3, 1923 at the University of Frankfurt. The Institute came into being as a response to Germany’s political struggles that eventually saw the rise to power of Nazi Germany. The Frankfurt School was made up of educators that advocated the neo-Marxist social theory, an approach that incorporated elements of critical theory, psychoanalysis, sociology and others. Among these, critical theory was the term most widely associated to the Frankfurt School (Cowen, 2003). The Frankfurt School also challenged the concept of meaning and other traditional forms of rationality in the Western world (Darder et al., 2003). Basically, critical theory critiques the society in the hope of changing it to the better.

This characteristic of critical theory is also evident in the critical pedagogy advocated by Paulo Freire, who is recognised as “the most influential educational philosopher in the development of critical pedagogical thought and practice” (Darder et al., 2003, p. 5). His best-known contribution to critical pedagogy is the banking concept of education in which the teacher is the ‘bank’ and the students are the empty ‘accounts’ waiting to be filled by the teacher (Freire, 2003). By placing this concept in context with educational theories and practices, Freire established the foundation of critical pedagogy. Freire addressed not only issues of methodology and teaching practice in his writings, but he also dealt with issues of power, culture, and oppression, all placed in the context of schooling (Darder et al., 2003).

Postmodernism is a problematic term to define, given that many theorists use it to categorise their work. Postmodern critical educators encourage their students to have diverse responses to classroom discussions, responses that cannot be anticipated in advance not even by their own teachers. Such situations are seen by postmodern critical educators as opportunities for creating a forum for discussion that allows and emphasises differences (Giroux, 1994).

Critical pedagogy evolved from the need to put in order radical theories, beliefs, and practices that contributed to the emancipation of democratic schooling in many schools, especially in the United States. The term ‘critical pedagogy’ was first used by Henry Giroux in his book, Theory and Resistance in Education, published in 1983. He argued that critical pedagogy was a movement that emerged from different social and educational radical movements and had the purpose of linking schooling to democratic principles of society and speaking up for the oppressed communities. Alongside with the work of other critical educators, such as Paulo Freire, belle hooks, and Peter McLaren, and many others, Giroux’s work had an important role in the revival of educational debates about democratic schooling in the United States (Darder et al., 2003).

Henry Giroux has argued that the way media represents youth is determined by the corporate culture it serves. Following the line set up by Paul Freire, in Henry Giroux’s opinion, educators have to address their students’ context of every day life. This cannot be done without first understanding the students. Because of the power that the media has in shaping the students’ cultural context, Giroux calls for a critical examination of the media and the cultural artifacts generated by it. In Giroux’s view, critical media pedagogy has the role of questioning the interests served by corporate media and provides resistance for those who are silenced and / or oppressed by it (Giroux, 2005). Critical educators, such as Henry A. Giroux, belle hooks, and Peter McLaren, based their critique of globalization, mass media, and race issues on critical pedagogy theory, suggesting possibilities for improvement and change.

The dialectical character of critical pedagogy, its immense possibility to empower students, the hidden curriculum and cultural politics are areas of great importance for educators who strive to create a critical classroom.

An important feature of critical pedagogy is its dialectical character. Dialectical theories consider that the problems of society are not isolated events, but that these problems form a network of connections between the individual and the society. As individuals, we are created by the social environment in which we live, and that is why the connection between individual and society is interwoven. Reference to the individual must, by implication, represent reference to society simultaneously. The dialectical aspect of critical pedagogy helps educators and researchers see the school both as a place of indoctrination through instructions and as a place of empowerment and self-transformation. Schools can, at the same time, empower students with regards to issues of social justice, but also can reproduce dominant class interests that have the purpose of creating obedient workers (McLaren, 2003).

Empowerment means knowledge and self-awareness. Empowerment is understood as the student’s ability to critically arrogate knowledge outside their daily experience, thus broadening their understanding of the world and themselves. Empowering also means teaching students critical skills that give them the necessary tools to question the dominant culture, and to transform the social order they live in, rather than just be part of it (McLaren, 2003).

Critical education theorists consider that the curriculum of a school is more than just a syllabus, a program of study, or a classroom text. The curriculum does more than that. It prepares the students for their future role in society as a dominant or a subordinate class. This is done through the forms of knowledge that the curriculum favours, often benefiting dominant groups and excluding subordinate ones. According to McLaren (2003), ‘the hidden curriculum’ is “the unintended outcomes of the schooling process.” (p.86) Critical educators have observed the fact that students are influenced not only by the standardised learning environment practiced by a certain school, but also by the rules of conduct imposed, classroom management and the pedagogical procedures adopted by the teachers. The hidden curriculum also includes the teaching and learning styles advocated by the classroom teacher, by the instructional environment, the schooling structure decided by the government, the teacher’s expectations and the testing and grading policy of the school. Thus, through the hidden curriculum, the students learn to comply with practices related to authority, behaviour and morality supported by the dominant class (McLaren, 2003).

The curriculum is also viewed by critical educational theorists as a form of cultural politics. The term cultural politics draws attention to the political consequence of the teachers and the students who are part of dominant and subordinate classes. This means that when researchers analyse contemporary schooling systems they also have to take into consideration social, cultural, economical and political aspects. A curriculum based on cultural politics links critical social theory to a variety of practices which help teachers deconstruct and critically examine traditions and educational systems that are dominant. It is also in the interest of critical educators to devise teaching systems and practices that empower students in life both in and out of school (McLaren, 2003).

This essay gave a birds-eye-view presentation of critical pedagogy. It started by outlining possible definitions of critical pedagogy, and presented the theorists who helped shape the theories that critical pedagogy is based on. It then looked further at some of most relevant feature of critical pedagogy to classroom practice. The writer of this essay acknowledges the fact the critical pedagogy is a complex teaching approach with numerous ramifications and that the present paper only scratches the surface.

References

- Cowen, H. (2003). The Significance of the Frankfurt School and Critical Theory. Proceedings of the BRLSI 7.

- Darder, A., Baltodano, M, & Tores, R.D. (2003). Critical Pedagogy: An Introduction. In A. Darder, M. Baltodano & R.D. Torres (Eds.), The Critical Pedagogy Reader. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Giroux, H.A. (1995). Doing Cultural Studies: Youth and the Challenge of Pedagogy. Retrieved October 7, 2008 from http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/courses/ed253a/Giroux/Giroux1.html

- Giroux, H.A. (1994). Slacking Off: Border Youth and Postmodern Education. Retrieved October 7, 2008 from http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/courses/ed253a/Giroux/Giroux5.html

- Freire, P. (2003). From ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed.’ In A. Darder, M. Baltodano & R.D. Torres (Eds.), The Critical Pedagogy Reader. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Kincheloe, J.L. (2004). Critical Pedagogy Primer. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- McLaren, P. (2003). Critical pedagogy: A Look at the Major Concepts. In A. Darder, M. Baltodano & R.D. Torres (Eds.), The Critical Pedagogy Reader. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Initially published in “Educatia PLUS” (pp. 246-250, Vol. VII, No. 2, 2011)

Photo source

thanks a milion.your works are great.

Nowadays i am realy intrested in CP ,the poineers & followers.send me useful mwterial in this field.